Interest in this period of history comes from our exploring the Pole Line Road, northwest of San Felipe. Read more in this article: HERE

Here are some details off the Internet, with links to read more:

1) From History of San Diego by Richard Pourade

While United States Cavalry patrolled the border and guarded nearby reservoirs, concern arose over the possibility of enemy use of airfields or bays of Baja California. Though Mexico had not declared war on Japan, the two naval bases and five airfields of Baja California were placed at the service of the United States, and a former president, General Lazaro Cardenas, was recalled from retirement to command the Pacific Zone. Troops in Baja California were reinforced, two battalions of 1,500 soldiers moving from Sonora through San Diego, by train, to Tijuana.

Early in January Presidents Roosevelt and Manuel Avila Camacho of Mexico had set up a United States-Mexico Defense Board and soon afterward Mexican aircraft began daily patrols from Cedros Island northward and Mexican gunboats aided in protecting minefields along the coast. Japanese farmers were moved inland from the coastal area.

After a conference in San Diego, on cooperation in defense, attended by General Cárdenas, controls were placed on fishing activities in the Gulf of California and the Pacific Coast north of Mazatlan. Soldiers and volunteer militia were assigned to construct telephone and telegraph lines and roads in the peninsula.

Mexico’s caution about entering the war vanished when two government-owned oil tankers were torpedoed in the Gulf of Mexico. On June 1, Mexico would join the United States in war against Germany, Italy and Japan.

The war seemed to erase all that was left of the troubled feelings that had existed along the United States border with Mexico as a result of the revolution which began in 1911. At one time 20,000 American soldiers patrolled the border from San Diego to Calexico and the Pacific Fleet stood by off Southern California. Tijuana was brought under attack by radicals, who were aided by United States citizens, but they were defeated by Mexican Army regulars. Later, United States forces directly intervened in Mexico by sea, to seize Vera Cruz, and by land from Texas. To Mexicans who never forgot that California and much of the Far West once belonged to them, the new actions were considered humiliating.

A National Guard regiment and artillery unit from Los Angeles were ordered to Calexico to guard the Colorado River water supply for Imperial Valley, which had to be diverted, at the time, through Mexican territory. What happened was recalled by a San Diegan, Lou Urquhart, then a lieutenant with the Guard. The governor of Baja California, Esteban Cantu, and Colonel Abelardo Rodriguez, later to become a governor and then a President of Mexico, posted crews with machine guns near Mexicali and opposite the Guard positions, presumably to resist any intervention. At a warning by Captain James G. Harbord, that he would use his artillery, Cantu and Rodriguez dismantled the gun emplacements and the chance of a direct clash was averted.

The era of cooperation between Mexico and the United States, initiated with Pearl Harbor, was extended into Baja California at the initiative of Commander Anderson, Public Information Officer of the Eleventh Naval District. General DeWitt, commanding the Western Frontier, would meet in Tijuana with his counterpart, General Juan Felipe Rico Islas, General de Division, Army of the Republic of Mexico. Mexican army officers would be treated at the Naval Hospital and Mexican fliers would train at the Naval Air Station. Contact would continue on an official and social basis, the latter through an organization known as “Mosqueteros de la Frontera” which attracted Army officers of Mexico and Navy and Marine Corps officers of the United States. Rodriguez later would maintain a second home in San Diego.

As part of the general scheme of filling in the gaps in the defenses of California after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Fourth Air Force had strongly urged the building of three landing fields for pursuit planes in Baja California and two staging fields, one near El Rosario and the other near La Paz. Time, and authority to use the fields for operations, were the important considerations. Both the War Department and the joint defense commission, when formally constituted, were agreed upon the desirability of the proposal, which the commission adopted as its Fourth Recommendation on 10 April 1942. After some backing and filling a joint survey got well under way and recommended three sites as primary airdromes-El Ciprés, six miles south of Ensenada; Camalu, just south of San Jacinto; and Trinidad, about eighteen miles south of La Ventura. Later, four other fields were surveyed. For three weeks at the end of June and in early July the War Department, on the advice of the joint defense commission, called a halt to all activity in connection with the airfields in order to give Mexican opinion time to crystallize and to give General Cárdenas an opportunity to make a decision. After authority was given to proceed with the plans and estimates for the original five airfields, General Cárdenas and especially General Juan Felipe Rico, the local Mexican commander, took hold of the project with enthusiasm and pushed not only the airfields but also a connecting highway down the peninsula. General DeWitt promised any help in materials and equipment that General Rico might need. The United States, General DeWitt thought, was committed to assist both projects, the roads as well as the airfields.

By the beginning of 1943, the War Department had begun to cool, although the Fourth Air Force still urged that the three northern fields, at El Ciprés, Camalu, and Trinidad, be constructed and tied to San Diego by connecting roads. In March the War Department rejected General Rico’s request for materials and equipment for the construction of the airfields. The Mexican section of the joint commission thus found itself in the position, in August, of arguing in favor of the United States Army undertaking a defense construction project on Mexican soil, while the American section was opposed. With the War Department unwilling to provide the construction materials because of the urgent needs of more active theaters of operations, the discussion became academic.

2) From The California State Military Museum

Arrangements were made between the U.S. Government and the Government of Mexico to allow joint teams of U.S. Army officers and Mexicans Army officers and soldiers to patrol the Mexican peninsula of Baja California. The teams were platoon-size units and patrolled all the way to the southern tip of the peninsula. There were persistent rumors early in the war that the Japanese might have secret air bases in Baja California, but no evidence of this was ever found. The American officers were required to wear civilian clothing and all U.S. markings had to be removed from U.S. Army vehicles and other equipment to accommodate Mexico’s neutrality laws.

3) From The Two Californias During World War II by Michael Mathes

This defense co-operation with the United States for the protection of the West Coast, notwithstanding Mexico’s neutrality, was greatly appreciated in California. Following the announcement of the patrol and fortification of Baja California, Senator Sheridan Downey stated before the Senate that “Mexico today gives us proof for the righteousness of our course. Mexico could have seriously endangered our military position in this war. Soon thereafter Cardenas optimistically reported from Ensenada that there were no Japanese bases or hideaways in Baja California.

Following this announcement, however, on January 2, 1942, Presidents Manuel Avila Camacho and Franklin D. Roosevelt, by executive agreement, set up the Mexico-United States Defense Board to study defense problems. Following the creation of this board, nine Mexican air patrols began daily operation in the Pacific from Isla de Cedros-northward, and Mexican gunboats protected United States minefields along the coast.

Due to the severance of Mexico’s diplomatic relations with Japan the preceding December 8, all Japanese along the Mexican coast were ordered to move one hundred kilometers inland between December 31 and January 15. This time limit was extended, however, and defense measures were given priority planning.

Following his defense conference with the governors of Baja California, Sonora, Sinaloa, Nayarit, Jalisco, Michoacán, Guerrero, Oaxaca, and Chiapas, held in Mazatlán from January 18 to 20, Cárdenas went to San Diego where from January 23 to 28 he attended joint conferences on defense. The results of these conferences were strict controls on fishing, joint air and sea patrols north of Mazatlan, and daily reports to San Francisco by Colonel Luis Amalillo Flores, military attaché in Washington. In Baja California, regular troops and one thousand volunteer militia, all under orders from General Macias Valenzuela, were assigned to the construction of roads, telephones and telegraph lines, and gun emplacements. To serve as a command post and civil defense center, the Hotel Riviera del Pacifico in Ensenada was taken over as an emergency measure.

Reports from these newly established Baja California defense stations of Japanese aircraft and submarines along the California coast in February of 1942 brought a new surge of military activity in Baja California. Following many days of intensive patrol, Cárdenas reported that neither submarines nor aircraft had used Baja California as a base; however vigilance and restrictions would be increased. The results were the arrest of eighteen Japanese within the one hundred kilometer restricted zone and the surveillance of firms on the United States Proscribed List of Certain Blocked Nationals.

Notwithstanding active co-operation with the United States throughout the early months of 1942, Mexico had remained cautious regarding formal commitment to the conflict. However, following the torpedoing of the Pemex tankers Potrero del Llano on May 15 and Faja de Oro on May 20, the question of war was placed before the National Congress. On June 1, following a near unanimous vote, President Manuel Avila Camacho decreed that “The United Mexican States are found in a State of War with Germany, Italy, and Japan.

4) From https://the-wanderling.com/hoover_dam.html

“The V-2 hauling U-195 and 219 transferred the major item of their quote cargo, unquote, over to the U-181 in the Indian Ocean with the U-181 then taking it toward the Pacific. There, at a point undisclosed the U-181 was met by the infamous long-range ghost-like Japanese submarine I-12. The I-12 took over eventually ending up at the La Palma Secret Base sometime around mid-December, 1944. After a minor shakedown and testing in and around the secret base and just off shore by German crew members, the cargo was taken a 1000 miles north by the powerful trans-oceanic I-12 to the mouth of the Sea of Cortez that lies between the Baja Peninsula and mainland Mexico, then another 1000 miles north to Isla Angel de la Guarda, also called Archangel Island, off Bahia de los Angeles — or one of the other smaller islands nearby and hidden in a cove.”

Toward the top of the page I write that according to the IVth Interceptor Command, through research by authors John R. Monett, Lester Cole and Jack C. Cleland in their book Harbor Defenses of Los Angeles in World War II, reported that in December 1941 several enemy planes were believed to be hidden near the desert communities of Indio and Brawley in the Imperial Valley of California and that an air attack by German airmen from across the border where additional planes were under cover, was immanent. I also wrote that the attack, which everybody must know never came off, even though all units of the harbor defenses were put on alert and ready for action.

Then, by spring of 1942, General George S. Patton Jr. had moved into the Indio and Brawley area and put into place a desert training center for his tanks and armored equipment hindering any further small scale attacks from the desert or Mexico. Near the end of April or early May of 1942, U.S. Military Intelligence learned the Japanese had put to sea the small but fast Japanese 5th Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Hosagaya Boshiro and consisting of two light carriers and a seaplane carrier at its core, along with support ships; two strike forces, and his flagship group, comprising a heavy cruiser and two destroyers, protecting supply ships — configured in what appeared to be a potential invasion force. By June 3, 1942 Patton was convinced the fleet’s final destination was to invade Mexico by landing on the beaches of Baja California, then move north into California. Patton positioned almost his full compliment of officers and men, albeit not yet anywhere near fully trained, within striking distance right on top of the border to move south within minutes to meet any invading Japanese force. The suspected Japanese invasion fleet eventually landed on Kiska Island in the Aleutian Chain on June 6, 1942.

5) From https://the-wanderling.com/jeep.html

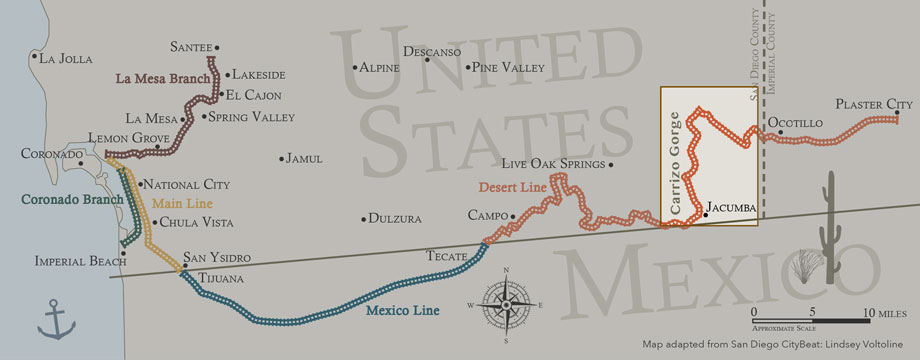

On one of those Sunday mornings, a number of those sailors that had been stationed in San Diego at one time or the other brought up the fact that a weird and little-known railroad sometimes called the Southern Pacific’s San Diego and Arizona Eastern Railway and sometimes called by other names that used to run passengers into Mexico from San Diego and clear over to the desert near El Centro and back that all of them had used going into and out of Mexico from San Diego had shut down passenger service after years and years of running the service.

They came up with this big idea that turned out to be probably my biggest jeep adventure of all time. One of the sailors said he had seen where a jeep could be adapted to run on railroad tracks so we should take the ranch jeep down there, fix it to ride on the rails, and drive it into Mexico and the U.S. One of the other guys piped in saying that during the war, at least during the early part of the war, 1942 or so, the Army had regular patrols along the railway looking for saboteurs and that he had met a soldier that said that’s exactly what they did, fixed up jeeps so they could run on the rails. Everybody figured, what the heck, if the Army could do, so could the Navy and most likely, even better.

The next thing I knew a bunch of sailors with Leo driving and me tagging along headed south toward the Mexican border. According to Leo we would be crossing the border into Mexico at Tecate about 20 miles south east of San Diego. Leo said he knew we could pick up the railroad tracks in an isolated area a short distance east out of town. Everybody was jumping up and down all for it like a bunch of drunken sailors — of which they were. Leo figured the only way we could get away with it was for the whole thing to be done on the QT, especially me not saying one word to my stepmother. Not worried my stepmother would stop it, but not wanting to be blocked from going I most dutifully complied. Once we decided to go and head for Tecate the whole thing was approached it like a secret mission.

6) From Scott Manning: What if Japan Invaded Mexico in June of 1942?

In the summer of 1942, US intelligence was reporting that Japan had a large invasion fleet in the Pacific. Due to the weakened security around Japan’s communications, the Allied forces knew the target was Alaska. Even better, the Allies knew this was a diversionary tactic while the Japanese focused on their real target: Midway.

Not everyone in high command was convinced though. Some saw this as a feint and with good cause. The Japanese had used numerous feints before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Targets such as Hawaii and San Francisco were discussed as possible destinations of a larger attack.

One such man who saw the whole thing as a deception was General Patton. In the summer of 1942, the US general was in charge of the I Armored Corps based out of the Southern Californian desert. He had around 20,000 troops practicing maneuvers throughout California, Arizona, and Nevada. This area of America best resembled the desert of North Africa where the Allies needed help fighting German Field Marshal Rommel.

Upon hearing the news that the Japanese had an invasion fleet somewhere in the Pacific, General Patton put his troops into high gear. He believed the most logical spot for the invasion fleet was Mexico. America’s southern neighbor had just joined in the war against Japan in May. The general told his troops, “Mexico will not be able to stop any invasion. The beaches of this Lower California Bay are superior for landing a large invasion force. Several hundred thousand men could be landed on this beach! It will be easy to run through Mexico. Los Angeles is only a short distance from Mexico.”

The goal of hitting Orange County and Los Angeles would be to take out the two largest producers of aircraft for America at the time. It was all too obvious for General Patton, “Any fool knows this would be the best objective for the Japs. If they knock out our aircraft production and get a force into Los Angeles, we are in for a long war. We will prepare to meet the bastards on the beaches of Mexico!”

7) From https://the-wanderling.com/hellcat.html

With a military vacuum in the area, the Germans, who as early as August 1942 secretly had a physical presence of at least two submarines in the Sea of Cortez, returned late in the year of 1944 after the pull-out of the troops associated with the CAMA because of an avid interest in Hoover Dam. Matter of fact it seems at least one U.S. Navy F6F Hellcat was dispatched from the Imperial Beach NAS south of San Diego to intercept one of the Axis subs in the Sea of Cortez as the remains of an apparent shot down Hellcat are still visible in the surf of Sonora, Mexico at extreme low tide.

An American by the name of Jerry Kelly, sometimes of Bowie, Arizona, sometimes of Las Dunas Santo Tomás, Mexico, tells me he has come across the wreckage of the Hellcat on several occasions. Not long after an on-his-own coming across the parts of the downed craft scattered around in the low tide sand for the first time — and with the sea once again cooperating in it’s cycle of ebb and flow, he was back walking the debris field when an old man came by in a pickup driving in the sand of the low tide. The old man told him the wreck happened sometime in 1942 or 1943. Although the plane washed ashore later his father rescued the pilot who told him “they” had bombed a German ship or submarine although he wasn’t sure of which. Who the “they” were other than the pilot of the downed Hellcat is not clear, implicating through the choice of words that more than just the downed pilot was involved in some sort of a multiple person or multiple craft mission over the Sea of Cortez. A few weeks later American troops arrived in Puerto Peñasco, also known as Rocky Point, about 75 miles north, taking trawlers down to the site, loading up many large crates and boxes and returning to the states with them.

Kelly also tells me there is a place about 3 miles south of Santo Tomas that has been known as ‘Germans Point’ for 50 years. Old timers in and around the Santo Tomás area tell the story about an old Nazi that had a fish shack there who was said by him to have come off a German sub in the war…..he went back to Germany in the 70s or 80s…..a good fisherman who always paid for his supplies with gold

8) From this page, HERE

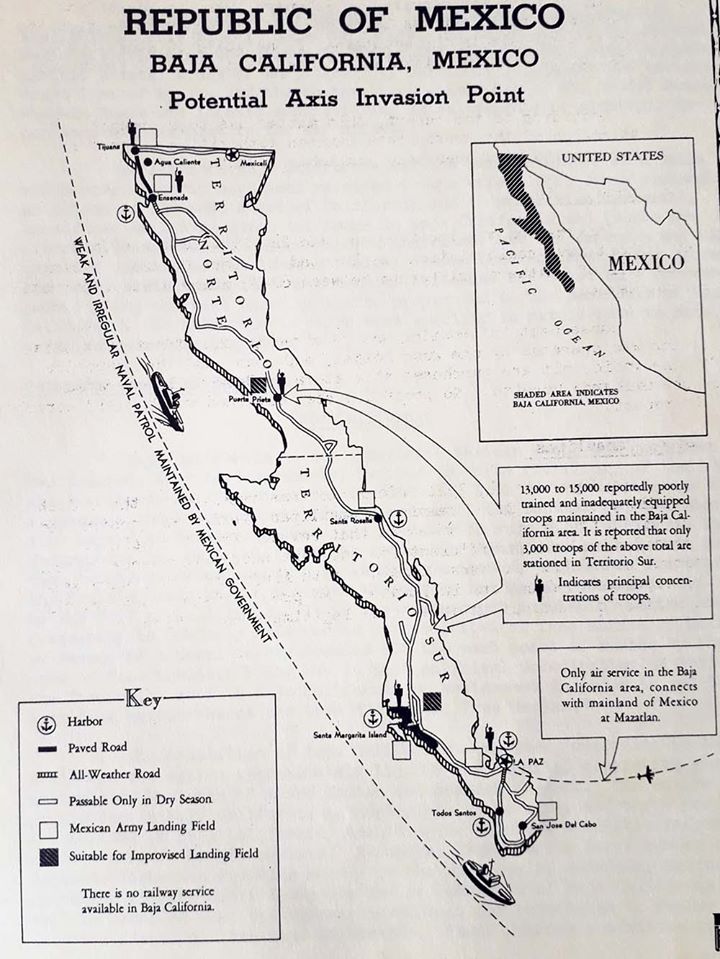

American WWII Air Defense Radar Stations

(1942 – 1943), State of Baja California (Norte)

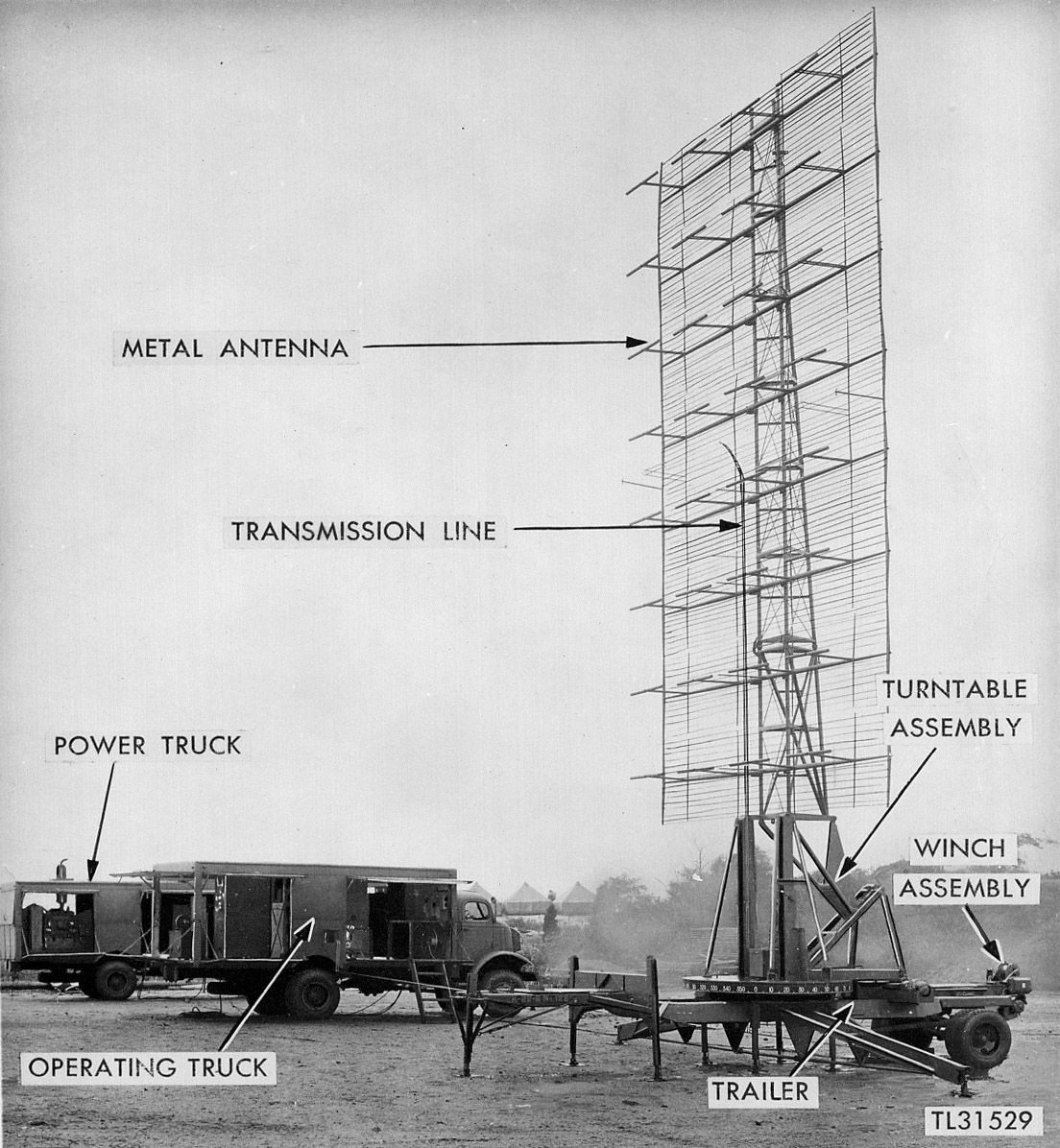

During the early years of WWII the U.S. Army built and manned at least three SCR-270 early warning anti-aircraft radar stations along the coast of Baja California Norte, operated by the 654th AWS Company, to protect the southern approaches to San Diego, California. Known sites include Station B-92 at Punta Salispuedes, located 22 miles northwest of Ensenada (later moved to Alisitos, 36 miles south of Tijuana); Station B-94 at Punta San Jacinto, 60 miles south of Ensenada; and Station B-97 at Punta Estrella (Diggs), south of San Felipe on the Gulf of California (aka Sea of Cortez).

More from Richard Pourade on the radar stations:

Two of the radar stations were set up and began operations during the first week in June 1942 and the third a month later. At each, one officer and twenty-five enlisted men were stationed to operate the set and train Mexican military personnel in its use. The equipment itself was turned over to the Mexican Army under lend-lease. By the end of August the Mexican troops had taken over the operation of the sets, and the Americans had withdrawn except for a small detachment of five men and one officer at each station. The coverage provided by the three sets was far from complete, but even as early as October 1942 the War Department was breathing more easily and saw no need to install additional equipment.

By the summer of 1943 retrenchment had become the order of the day in Baja California. All Americans were withdrawn from the radar stations except for one officer and three enlisted men, who were left in Ensenada primarily for liaison purposes. All requests for additional equipment had to be refused. By mid-May 1944 the Commanding General, Fourth Air Force, reported that he no longer considered the three radar stations necessary for the defense of California and, much to the dismay of both Navies, who wished to have the sets in operation for air-sea rescue work, operations ceased about the first of June. When, at a meeting of the defense commission, Admiral Johnson protested against a Mexican Army proposal to move the equipment to Mexico City, General Henry was obliged to state that the War Department’s policy of retrenchment remained unchanged but that there would be no objection to the Navy’s supplying and maintaining the operation of the sets.

For the remainder of the war, the Army had no further responsibility in the matter. One station resumed operation with gasoline and oil supplied by the Navy. The other two were moved away. During the two years they had been in operation, the stations performed a useful function. They had closed all but a small gap in the network around the San Diego-Los Angeles area. Anticipated language difficulties failed to materialize to any great extent, and valuable training in the use of highly technical equipment was given our Mexican ally.

9) Japanese Base in Mexico During WW II

” When we went over on Lower California, some of the Indian fishermen had discovered this break off cliff face, and it had left a a great big round harbor in there and deep water. It made a perfect camouflage. The Japanese had been using it for a submarine base. It was perfect for that. You could go in or out at either end and if you were a quarter of a mile off shore, you couldn’t see it. It just looked like the cliff face.

“I had a Yaqui friend who was a demolition expert. He was the meanest little bastard you ever saw. He had a company of Yaquis and asked me if I wanted to have some fun, and I told him yes. So we went over on Lower California and marched into this place at night. We sneaked up on this outfit. They had some sentries up on top. We sank two of their boats. The Yaquis cut their throats. They killed the Japanese sentries with their knives. We went on and got down there and got aboard the ships and had a scuffle or two but finally got them all subdued and locked up in their cabins. We put explosives all over the boats and then went down and opened the sea cocks on these three trawlers and lit the fuses and we went back ashore. We set mines and everything else in these caves. When it went off, it looked as if that whole side of Lower California coast had blown up…” by Rufus Van Zandt from The Van Zandt Papers’ Japanese Base in Mexico.

10) Japanese-Mexicans in WWII and what U.S. did

In my search for more data on the radar base in San Felipe and the Telephone Pole Line and roads we built to San Felipe in 1942 for the defense of California, I found this article, and it was most interesting. The Japanese decedents in both the U.S. and Mexico did not get a fair break.

Here is just one part of the article:

“Furthermore, in March, 1942, the Mexican government allowed the entrance of US soldiers into Cd. Juárez with the purpose of searching several residences of Mexican Japanese families. As a result, 15 Japanese and Mexican Japanese men were interrogated in the Mexican garrison by Mexican and United States army officers.“